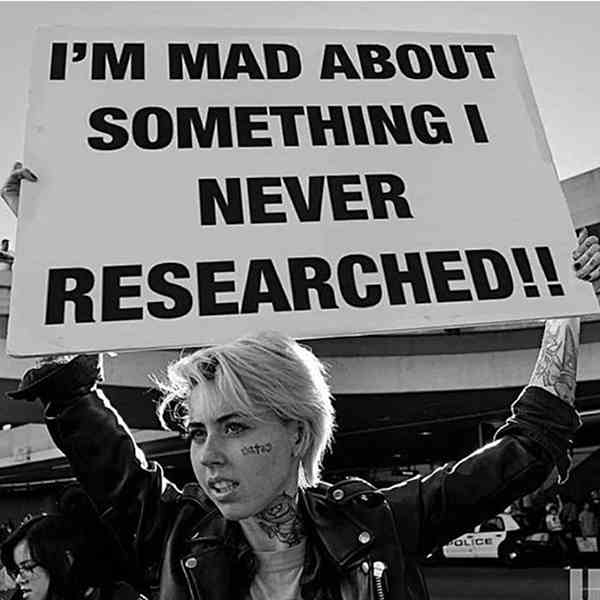

I’m starting a new feature in my Facebook newsfeed called “Meme Watch.” It will periodically investigate the accuracy of those pesky posts that pop up, devoid of sources, originating from questionable sites, claiming outrageous things or spinning conspiracies and rumor.

Why do this?

Because, frankly, I hate these memes. I think they’re dangerous. As a retired journalist and webmaster, they represent a nightmare convergence of the worst of both worlds. They drive me crazy.

What’s a meme? It originally meant “a unit of cultural information spread by imitation.” The term (from the Greek mimema, meaning “imitated”) was introduced in 1976 by British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his work The Selfish Gene. The most prevalent versions of a meme today are seen in Twitter and Facebook posts and reposts.

(For a deeper understanding of how online memes are spread, watch the Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma.”)

My attempts to correct the mistaken or misquoted Facebook posts of my friends and family have not been well received, to put it mildly.

Spoken or unspoken, their responses have been along the lines of, “Who cares! Who in the hell do you think you are! Just lighten up!”

So, I had to stop and think. Am I just trying to be a smart ass, a know-it-all?

I wouldn’t put it past me. A couple of years ago, I was awakened to how my own online satire and humor could cross lines into unkindness and even slander.

But I recently remembered something that I’d forgotten, and it makes me even more determined to label untruth when I run across it.

So, instead of leaving comments on other people’s feeds (you’re welcome), I’ll be dissecting memes on my own feed, under the label “Meme Watch.”

I’m writing this rather LONG, personal essay (or rant), to try to get all this straight in my head. I hope you’ll indulge me.

Meeting My First Meme

When I was a young teenager, we would travel to Louisiana to visit relatives. At the Texas-Louisiana border we would pass a billboard that said “Impeach Earl Warren!” in giant letters. Warren was the liberal chief justice of the Supreme Court that ruled on Brown v. Board of Education, which desegregated public schools. The billboards were put up by the John Birch Society. But there was another billboard further on, with a large, grainy photograph of a young Martin Luther King Jr. sitting with a group “at a Communist training camp.”

This was probably the first of what we would call today a “meme” – but it was a really slow-moving meme. It didn’t pop up in front of you, you had to go to it.

There was no internet. I assumed that if it was on a billboard it must be true. Surely somebody would make them take it down if it wasn’t. I pictured King in Russia or maybe in an East European country getting his instructions on how to subvert American freedoms. I accepted the billboard’s message because it agreed with my own inclination, which was in turn influenced by my parents’ conservative political beliefs.

I even remember telling my girlfriend years later about that billboard during one heated discussion on current events. This meme influenced my thinking about the Civil Rights Movement for years until I got into college and encountered other, more diverse, alternative opinions.

I think about that billboard as I scroll past the hundreds of memes posted on Facebook every day, making often unbelievable claims.

If I’d had access to the internet as a teenager I could have looked up that billboard and checked its accuracy. Turns out, King was not in Russia. The photo shows him at Highlander Folk School, a Tennessee social justice training center. King was asked to participate in Highlander’s anniversary celebration in 1957. While attending the celebration, an undercover agent sent by the Georgia Commission on Education took a photograph of King, which was used in the billboard. The concept for the school was based on Lutheran “folk schools” in Denmark. The founder, Myles Horton, was indeed a socialist, but not a Communist. He was a former student of theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and a follower of the liberal “social gospel” theology, and the place was a center for training labor organizers and, later, civil rights workers like Rosa Parks and King. (The FBI also tried to paint this school and King as Communist, but J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI has itself been discredited now, and his illegal smear campaign against King exposed).

The billboards were put up all over the South by the White Citizens Council, which today would be listed as a right-wing terrorist group. For instance, one White Citizens Council member, Byron De La Beckwith, murdered civil rights worker Medgar Evers in 1963. The White Citizens Council paid for his legal defense. Beckwith was finally convicted to life in prison in 1994.

The Facebook Accelerant – ‘Attraction to Divisiveness’

Social media is now ground zero for spreading misinformation. Many people only get their news by clicking on Facebook posts from their favorite talking heads at Fox News or MSNBC, or from memes detached from any news source.

Jeff Orlowski, director of the Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma,” told the Guardian newspaper that a largely ignored internal memo to senior executives at Facebook in 2018 explains that “Our algorithms exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness.” Watching or clicking on one meme or video or post will trigger an even more extreme version on the same subject to pop up.

Orlowski concludes, “If two sides are constantly fed reflections of their pre-existing ideologies and outrageous straw men of opposing views, we will never be able to build bridges…”

Facebook, it seems, is designed to nourish our basest tribal instincts.

Real-World Harm

Unsubstantiated rumors, reposted and retweeted, can cause real-world harm. Here’s an incident that perfectly reflects the problem:

In late May, a Twitter account labelled @Antifa_Us threatened to take its anarchy and rioting away from cities like Seattle and into the suburbs, and featured a raised middle finger emoji to America. Donald Trump Jr. retweeted it on his instagram account, adding “Absolutely insane!”

Twitter discovered that the account had no connection to Antifa, the left-wing anti-fascist movement, but was posted by a US-based white-supremacist group called Identity Evropa, one of the organizers of the infamous 2017 neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Va. Twitter pulled the account. But it was too late, the tweet was already spreading rapidly. Seth Larson, the manager of a firearms store in Sequim, Wash., had reposted it, and when he heard of a planned Black Lives Matter protest in his area, he worried Antifa rioters would be there too. Using Facebook Live, he put out a call to arms to his friends. Some responded: “Lock and Load!”

This started a chain reaction, ending when a traffic jam of angry, gun-toting townspeople in pickup trucks, SUVs and ATVs blocked and harassed a bus with an innocent family of brown-skinned tourist campers with their two dogs, forcing them to flee, and finally – when trees were felled blocking the road leading out of town and warning shots were fired – filled them with genuine terror.

Once it became clear there were no Antifa incursions, Larson admitted to the police that he had been wrong and had “knee-jerked” about Antifa. But later, talking to a writer for Wired Magazine, his conspiracy thinking kicked back in. The police were “just falling with the same liberal quid pro quo of ‘Let’s cover this up.’” Because he couldn’t trust Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, he said, he couldn’t trust the truth of whether that Twitter account was really posted by a right-wing militia group.

“Just an FYI,” Larson added. “It wasn’t just a family on a camping trip. There were seven grown men on the bus.” Where’d he hear that? “It’s local knowledge. Let’s just put it that way.”

Gullibility of the Faithful

My fellow Evangelical Christians seem to be very susceptible to Facebook’s algorithms. And this gullibility predates the Internet.

In the late 1960s an article was widely circulated for years about a NASA computer that proved Joshua had made the sun stand still for a day as described in the Book of Joshua, Chapter 10. It was not true.

A petition circulating since 1975 to stop the atheist Madalynn Murray OHair’s non-existent attempt to get the FCC to ban religious broadcasting continues to show up periodically even today. It never was true. These print memes crossed my desk literally weekly when I was a reporter for a religious newspaper.

But those were memes in slow motion, arriving by mail. Today they come fast, one after another, and then disappear, leaving only an untraceable, subliminal nudge in the direction intended. Who originally posted it? What is the source? Is anybody else reporting this conspiracy? What did it actually say, can you even remember?

The general response is, “Who cares.”

One brand of Christianity is especially primed to believe fake memes.

“Christian nationalists have indicated over several studies that … they are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories, more likely to distrust the media and more likely to distrust scientists and feel like there’s some kind of conspiratorial agenda that is behind all of that,” according to Samuel Perry, associate professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma and co-author of Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. Christian nationalist views were also a striking predictor of affinity for xenophobic or racist arguments, he said.

“Christian Nationalist” is the label sociologists assign Christians who believe the federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation, and that the government should advocate Christian values. They disparage the concept of separation of church and state. The term describes those who want to fuse American civic life with Christian identity, and who believe the U.S. is under cultural threat.

These are probably also the same people who are most cavalier about the truth in the memes they repost.

I really wish I could ignore all this, but I can’t.

I do get it, though. For many people, Facebook is strictly a means of entertainment. It’s exhilarating and fun to find a meme that reflects your viewpoint, share it on your newsfeed, and see people “liking” it. It becomes a form of confirming fellowship among your community, and consequently affirming your own opinion.

But I believe we are seeing the concept of truth eroding before our eyes.

Humility in the Search for Truth

Humility is a requirement for an honest pursuit of truth, because we humans always seem to be a step behind.

Plato compared our understanding to watching images flickering on a cave wall, while actual reality was going on outside in the sunlight.

On the surface, identifying truth seems pretty simple. The “correspondence theory” of truth asserts that a true proposition is one that corresponds to fact – to some aspect of reality. Aristotle summed up the concept: “To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true” (Metaphysics 1011b25).

Well, Duh!

But philosophy also speaks of subjective reality – i.e. what we experience – being different from objective reality – what’s “really” going on.

Humans never are able to have “all the facts.” Our understanding is limited by the size of our brains, our short attention spans, our education, and our brief lives. Socrates warned us that true wisdom comes from “knowing that you know nothing.”

It’s expressed in a Christian context by Anne Lamott: “The opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty. Certainty is missing the point entirely. Faith includes noticing the mess, the emptiness and discomfort, and letting it be there until some light returns” – From Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith.

The more we find out, the less certain we are about what we know. As the island of knowledge increases, the shoreline around it of the unknown grows too. Objective reality seems to be as hard to pin down as Schrödinger’s cat. That famous quantum physics theory, later backed up by experiments, proposed that two versions of reality can exist at the same time, at least on the subatomic level.

But there’s a limit. In fact, in a strange bleed-over from quantum physics, Americans seem to have assumed that the quantum “many-worlds theory” of reality also applies to everyday events. But in order to function within our commonly shared experience, two or more competing versions of reality cannot be sustained.

We can’t “agree to disagree” about what someone actually said or did, for instance, when witnesses, recordings or video evidence exist to confirm the fact.

(Soon, however, AI-enhanced “deepfake” editing will make even that evidence suspect. That’s why this subject is of vital importance).

Our opinions and beliefs are always uncertain until they merge with the certainty of fact. We all filter our perceptions through our theories, expectations and desires. Even strongly held religious beliefs retain this difference between faith and fact. All I’m asking is that we be aware of that, and be willing to admit we might be wrong.

In fact, to fairly evaluate something, we must be able to “hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function,” to quote F. Scott Fitzgerald.

For some people, though, that threatens their very identity.

The best way to nail down the truth is to triangulate on it, using several different sources or proofs or viewpoints. A three-dimensional truth is better than a one-dimensional version. But we’re not taking the opportunity to even stand in someone else’s shoes. It’s really a refusal, rather than a failure, of imagination.

Politics and Partisanship

Our current dilemma has only been deepened by having a President who enjoys carelessly spreading falsehoods.

This has spawned a number of books claiming we now live in a post-truth, “misinformation age.” Here’s a blurb from Nathan Bomey’s book, After the Fact: The Erosion of Truth and the Inevitable Rise of Donald Trump, which analyzes our society’s increasingly tenuous commitment to facts:

“On Facebook, we present images of our lives that ignore the truth and intentionally deceive our friends and family. We consume fake news stories online and carelessly circulate false rumors. In politics, we vote for leaders who leverage political narratives that favor ideology over science. And in our schools, we fail to teach students how to authenticate information.”

Just to be clear, Democrats are part of the problem, too. A few recent examples:

When Joe Biden claimed that Trump’s tax bill gave companies “a reward for offshoring jobs,” The Washington Post’s fact checker noted that for some companies that might be true, but for others, the law would make it actually harder to “offshore” jobs. It’s an example of a very complex question over-simplified to make a political point.

Another example is a Biden campaign ad that makes the case that President Trump played down the coronavirus threat to the American public, while he was taking it seriously in private. The Post pointed out the ad uses a manipulated video and quotes from later on in the pandemic — after Trump had shifted his tone publicly on the threat of the virus. The ad also repeats the Trump quote saying the coronavirus was “a hoax,” although Trump’s original statement clearly referred to the Democrats’ politicizing of the coronavirus as the hoax.

Everybody’s playing the game.

Rumors, celebrity scandals, UFO sightings and hoaxes all used to be confined to the National Inquirer at the grocery check-out line. We used to rely on the press to vet, sift and sort out the truth for us. What happened?

Newspapers, the Vanishing Gatekeepers

Early American newspapers were lively providers of local news, event announcements, death notices, letters from across the ocean, local advertising, and – importantly – diverse political opinions. They helped galvanize support for independence. Written into the Constitution’s Bill of Rights, “Freedom of the Press” granted newspapers an honored place among the new country’s sacred institutions.

But printing is a business, after all. Even in the early Republic, newspapers published harsh invective against political opponents. Competition eventually gave rise to more political partisanship, sensationalist reporting, circulation wars, “yellow journalism,” muckraking and scandal mongering.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson judged newspapers in their day to be full of lies.

But at the beginning of the 20th century, the founding of schools of journalism began to turn the press into a profession, with ethical standards, professional societies and a focus on accuracy and fair reporting. Impartiality and objectivity became the ideal. Newspapers, and later the three TV networks, became gatekeepers of news and events. Walter Cronkite became the “most trusted man in America.” The high point for American journalism was probably the effort by The Washington Post to uncover the Watergate scandal.

All that began to change with the expansion of cable news networks in the 1980s and a 24-hour news cycle that was hungry for “content,” controversy, sensational stories and aggressive political argument and opinion.

With the Internet offering news for free, and classified ads being replaced by Craig’s List and Ebay, the print press lost both its subscription and advertising income base at the same time. Thousands of newspapers, magazines and other print media died or dropped out of sight.

Our local paper, The Dallas Morning News, used to be on everyone’s doorstep each day. After a number of layoffs and pay cuts in the 2000s, it continues, but in a humbled and weaker form, while its proud building in downtown Dallas, where my father worked as a reporter for 40 years, stands empty, ready to be turned into a mixed-use entertainment center. Dallas’ other paper, the Times Herald, closed in 1991.

This cycle has been repeated around the country, leading to a dearth of vital reporting on local government.

Nixon and ‘The Media’

“The media” as a general term for what we now call “the Main Stream Media” wasn’t in common use until the Nixon administration. He felt that to refer to journalists as “the press” ceded them an emotional upper hand, an aura of rectitude and First Amendment privilege.

William Safire, who was a speechwriter for Nixon, describes in his memoir, Before the Fall (1975), how the administration pushed the term “the media.” In the White House, he recalls, “The press became ‘the media’ because the word had a manipulative, Madison Avenue, all-encompassing connotation, and the press hated it.” Nixon declared to his staff that “the press is the enemy” a dozen times in Safire’s presence.

The concept was not new. Nikita Khrushchev, in his memoirs, observed that Joseph Stalin referred to “everyone who didn’t agree with him as an ‘enemy of the people.’ ” This sentiment was echoed again by President Trump, who in 2018 labelled the press “enemies of the people.” He referred to reporters as “scum,” “slime,” and “sick people.” Now, “Main Stream Media” has stuck as a demeaning term, referring basically to any source offering facts that don’t comport with one’s own views.

My dad would have understood this attitude. When President Kennedy was assassinated in our city, the world’s press poured into Dallas, rudely took over the press room at City Hall where he worked as a police reporter, spilled coffee and put out cigarette butts on his desk, and pushed and shoved their way past each other covering the biggest crime story of the century. My dad called them all “the Yankee Press.”

No doubt, some of the problems of big media have been caused by this public perception of arrogance over the years by the media “coastal elites.” But the harm done has been worse than their hubris.

Rise of the Fact Checkers

One result of all this is there are no more reputable gatekeepers or standard bearers that the public feels it can to turn to.

And as of 2019, nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of Americans from all political affiliations say news organizations favor just one side of political and social issues they are covering.

Because the public was left without an agreed-upon authoritative source of news and truth, internet fact checkers began to try to fill the gap. The oldest fact-checking site, Snopes, started even before the internet in 1994, investigating urban legends.

Snopes has been joined by Politifact, ProPublica, Factcheck.org, the conservative Newsbusters.org and a host of others.

But there has been no common agreement about fact checking. It still divides sharply along partisan lines.

Political analysts worry that democracy and freedom of the press are increasingly threatened because Americans “do not share a common baseline of facts” in an online environment where people can pick and choose their news.

Sophists Gone Wild

Without authoritative sources of news to turn to, the field is left wide open for propaganda and “spin” to rule the day.

The history of playing fast and loose with the truth is fascinating.

We see it all the way back in Genesis with the serpent’s partisan “spin” on God’s command in the Garden of Eden. But let’s start with the Sophists, orators in Ancient Greece who believed there was no absolute truth. They charged high fees for teaching rhetoric and dialectics to help their students craft arguments, sometimes deceptively, that aroused emotions and persuaded the populace. Through speech, they claimed, you could persuade people into believing …anything.

In the democracy of Athens, the power to persuade the crowd was highly valued, and often abused by demagogues. This is one reason pure democracy was feared even by some of our founding fathers – the power of the mob could be roused through deceptive sophistry without some built-in republican safeguards.

Because of their powers of persuasion, Sophists also became sought after as the world’s first lawyers.

Publicity

The rise of a new class of modern Sophists tracked closely the rise of ethical reform by the newspapers and the press.

Teddy Roosevelt became the first U.S. president to make use of “publicity” through his bully pulpit of the presidency. Publicity originally meant transparency, laying bare the facts to the public. Roosevelt used this to expose corruption and further his reform agenda.

Progressive politicians like Roosevelt believed that if the wrongdoing of backroom politics or corporate malfeasance were exposed to the light of day by the press, the ensuing popular outcry would force the powerful to change their ways. He expertly coordinated with the newspapers to do this, which then led to reform legislation in Congress.

The idea caught on. Woodrow Wilson created the first wartime propaganda agency. Calvin Coolidge staged photo-ops. Herbert Hoover produced an elaborate campaign film. Dwight Eisenhower employed a White House TV coach.

The Spin Doctors

As the press began to expose wrongdoing, experts in “public relations” rose up to help industry and politicians counter the press – while at the same time using it – to frame their own versions of reality.

The father of both propaganda and public relations was Edward Louis Bernays, an Austrian-American nephew of Sigmund Freud. He helped the American Tobacco Company increase female smoking through a 1929 campaign that celebrated cigarettes as feminist “torches of freedom.” In his books Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923) and Propaganda (1928) he outlined how skilled practitioners could use crowd psychology and psychoanalysis to control the masses. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels read and used Bernays’ methods.

The first strictly political consultants were Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter, a husband-and-wife team that started Campaigns, Inc., in 1934. Together, they developed strategies like media advertisement buys and direct-mail campaigns that are still widely used in today’s campaigns. They helped kill Upton Sinclair’s run for governor of California by simply republishing his own statements from earlier in his career in favor of “free love” and socialism. Arthur Schlesinger called this the first all-out public relations “blitzkrieg” in American politics.

’Socialized Medicine’

In 1949 the American Medical Association paid the couple $350,000 to defeat President Truman’s proposed government-subsidized healthcare program. As part of their messaging, they began calling the plan “socialized medicine,” ushering in negative connotations and allusions to communism, playing off the Cold War paranoia of the time. After three years and the equivalent of $40 million, their campaign was successful. Government-subsidized healthcare – “socialized medicine” – was dead until the Medicare and Medicaid legislation in 1965.

The rise of public relations and advertising agencies in the “Mad Men” era led Vance Packard to warn in 1957 that a new breed was entering politics “to engineer our consent to their projects or to engineer our enthusiasm for their candidates.”

Books like The Selling of the President by Joe McGinniss (1969) and the 2006 book Politics Lost: How American Democracy Was Trivialized by People Who Think You’re Stupid by Joe Klein portray modern media politics as a big con job, in which shrewd managers regularly mislead the public.

Klein’s book opens with a vignette of Robert Kennedy delivering his spontaneous, heartfelt paean to Martin Luther King Jr. on the night of King’s assassination. Klein describes this as “the last moments before American political life was overwhelmed by marketing professionals, consultants, and pollsters.”

The earliest recorded “spin room” was set up by the campaign of Ronald Reagan after a debate with Walter Mondale in 1984. The rest is history.

Spin doctors and “new Sophists” are now unchecked, free to influence the citizenry because of our constant exposure to social media.

All this is scary, without even factoring in the additional biases of foreign interference on Facebook from Russia, China, etc.

The Brain’s Defenses Against ‘Spin’

Although we’re on the receiving end of spin and propaganda, we’ve also got our own biases that influence us, and also protect us.

In fact, “spin” struggles against another human trait – selective perception. We seek out and remember facts that agree with our own worldview and tend to ignore the rest.

Social science research shows that the public actually has a great capacity to resist spin.

Scholars now recognize the phenomena of “selective exposure,” the tendency to seek out agreeable news; “selective perception,” placing trust in agreeable information while blocking out disagreeable information; and “motivated reasoning,” using logic to reach already desired conclusions.

We may worry that politicians will convince us of falsehoods, but the reality today is closer to the opposite: We’re so cocooned in our own ideological bubbles that it’s hard to convince anyone of anything.

When people become heavily committed or invested in a particular cause, their perceptions often change in order to remain consistent with this commitment.

An example of selective perception is the “hostile media affect.”

An experiment in 1985 – backed up by many others since then – showed unbiased news clips of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon to groups of pro-Arab and pro-Israel American students. The pro-Arab students felt the news programs excused Israel’s aggression. The pro-Israel students felt Israel was being blamed in those same news reports.

Inevitable Loss of Community

Distrust of the press reflects a broader collapse of trust in all institutions in America.

In a recent article in The Atlantic, David Brooks warns, “When people in a society lose faith or trust in their institutions and in each other, the nation collapses.”

“In 1964, for example, 77 percent of Americans said they trusted the federal government to do the right thing most or all of the time. By 1994, only one in five Americans said they trusted government to do the right thing. In 1997, 64 percent of Americans had a great or good deal of trust in the political competence of their fellow citizens; today only a third of Americans feel that way.”

It affects how we view strangers and even our friends.

“In 2014, according to the General Social Survey conducted at the University of Chicago, only 30.3 percent of Americans agreed that ‘most people can be trusted,’ the lowest number the survey has recorded since it started asking the question in 1972.”

Brooks notes that Alexis de Tocqueville in the 1800s discussed a concept called the “social body.” Americans were clearly individualistic, he observed, but they shared common ideas and common values, and could, when needed, produce common action. But now those common values are evaporating, and it will be extremely difficult to regain a sense of community.

This collapse of trust has allowed conspiracy theories to reign supreme.

Simple Facts Can Often Be Complex

My Dad used to tell me to “always prefer the simple to the complex.” I think he was restating Ockham’s Razor: “Entities should not be multiplied without necessity,” a problem-solving principle in philosophy generally attributed to English Franciscan theologian William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347).

(Interestingly, the quote above can’t be found in any of Ockham’s extant works, so a fact check would rate that famous quote as “possibly not true.” Hmm).

People do like simplicity rather than complexity. But more often than not, the context of a statement of fact is actually nuanced and complex.

“Facts” often contain a lot of subtle and complex details, assertions, opinions and debatable points. We have to sort through these in discerning the truth.

Some facts are “vaguely true” but are taken out of context. Some issues are far too nuanced to say definitively “this is correct” or “that is incorrect.”

Ambiguity is not always a negative. Unfortunately, ambiguity sometimes describes the extent of our knowledge, and defines things as they are.

Conspiracies – Complex Questions Often Have a Simple Answer

There is certainly one area where people don’t prefer the simple to the complex – conspiracies.

The history of conspiracy theories dates from at least early Roman times, surfaces in the Middle Ages with blood libels against the Jews, runs through the anti-Semitic “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” and on to modern theories about the Kennedy assassination, the Moon landing, HIV-AIDS and 9/11.

Today we have distrust and suspicion about Covid-19 statistics, vaccines and Black Lives Matter, to name a few. Hoaxes and secret backroom machinations are proposed to explain conflicting data.

A ‘Kind of Psychosis’

The psychology of conspiracy theories involves overestimating the likelihood of co-occurring events, and attributing intentionality where it is unlikely to exist.

Perhaps the best background to the current rise of conspiracy theories is the PBS Frontline documentary “United States of Conspiracy.” It focuses on Alex Jones and his influence on Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign.

Jones spent considerable airtime propounding a theory that the 2012 Sandy Hook mass school shooting was actually a hoax – that no children were killed, and paid actors were perpetrating a “false flag” conspiracy.

During a remarkable filmed deposition shown in that documentary, part of a lawsuit against him by Sandy Hook parents, Alex Jones admitted that he had spread hurtful, unfounded rumors, and blamed it on a kind of “psychosis” that came over him.

Seeing Patterns – From Apophenia to Anomie

Jones’ “psychosis” could be a more extreme form of apophenia, the natural human tendency to see patterns that do not actually exist.

Examples include the Man in the Moon, faces or figures in shadows, in clouds, and in patterns with no deliberate design, like in the swirls of cream in a cup of coffee, and the perception of causal relationships between events that are, in fact, unrelated. Apophenia figures prominently in conspiracy theories, gambling, misinterpretation of statistics and scientific data, and some kinds of religious and paranormal experiences.

I admit I’ve been prone in the past to believe conspiracy theories, but in my own experience, the “psychosis” was more akin to a sort of mild obsessive-compulsive disorder. I would automatically go through alternate explanations of events, pairing them with others in an effort to tie things together. Usually, reason would win out and the “conspiracy” would evaporate. This can be exhausting. But even now, while skeptical and free of paranoia, the temptation is always there to run with the theory. It’s still very appealing to me. Once bitten, I suppose, it’s hard to eliminate all the poison.

But the personal becomes the social, and multiplied millions of times over, extreme “apophenia” seems to be threatening our democracy.

The problem is that, as trust in institutions (and in each other) breaks down, it leads generally to greater “anomie,” a phrase from the social scientist Emile Durkheim. Taken from the Greek ἀνομία, “lawlessness,” anomie is a condition of a society when a loss of common norms and values leads to the breakdown of bonds between an individual and the community.

Individuals who feel alienated may reject conventional explanations of events, as they reject the legitimacy of the source of those explanations. Conspiracy theories proliferate and spread like a virus, or like a new religion, from person to person. And the internet multiplies the effect.

QAnon

Then, of course, there is the “One Theory to Rule Them All” – QAnon. It’s the Rubik’s Cube of conspiracy theories, almost impossible to describe, let alone solve. And it evolves. You can believe parts of it and drop other parts as events move along.

Don’t get me wrong. Conspiracies do occur. There actually were Soviet agents in U.S. government positions leading up to the Joe McCarthy era, for instance. And Communists made no secret that they conspired to take over the world by violent revolution. Al Qaeda and Isis really were conspiring to control the Middle East.

But sometimes the simple explanation is the correct one (remember Ockham’s Razor).

QAnon is too complicated to fully discuss here. Briefly, “Q” purports to be a government insider, and he proposes a secret cabal of elite politicians and celebrities who engage in cannibalism and pedophilia. He predicts that President Trump is about to arrest these evildoers at any moment.

One of the earliest Q “drops” was that Hillary Clinton was under house arrest already. That was in 2017. Because the theory is so adaptive, the fact that this was blatantly not true didn’t phase its followers at all.

But let’s consider why someone might buy into it.

We are susceptible to believing a conspiracy theory when we are in the posture of being victimized, when we perceive ourselves as powerless in some way. If I see myself as a victim, I am ready to receive the idea that I am being persecuted, that things are out of control, or events are being manipulated by unseen forces – whether it’s the big banks, the East Coast Elites, Hollywood, the Deep State, Big Pharma, multinational corporations, the medical establishment, or just an amorphous “them.”

One main factor is that by absorbing the intricacies of the theory, I become privy to secret information, and it makes me feel special. I have a mission, a crusade.

When unusual events, disasters or tragedies occur we seek, and even require, an explanation. We long to have some control, and the theory provides that.

But sometimes there is no explanation linking events or people together. There likely may be no one controlling things behind the scenes after all.

Perhaps You’ve Heard of My Good Buddy, George Soros

Take George Soros, for example. This shadowy Jewish Hungarian-born American billionaire figures in many, often contradictory, Internet theories.

I actually have a tenuous link to Soros. The first foreign exchange student we hosted in the early 2000s took advantage of a pro-democracy scholarship program funded by Soros’ organization in her former Soviet-dominated East European homeland. Without Soros’ program, she probably would not have been able to live for a year with us in America.

For a moment, consider the possibility that George Soros may not be an ex-Nazi (as in some theories) or a Communist (as in others) working to overthrow our institutions. He may just be a liberal billionaire trying to use his money to make the world a better place, according to his own private vision. We may not like Soros’ politics, but without the cloak of conspiracy, he becomes just another rich person rather than a demonic threat.

(Now that I’m “linked” to Soros, my credibility will forever be suspect).

A Thought Experiment

Here is a set of facts. See if you can put together a conspiracy linking them together:

My dad was the crime reporter covering the biggest crime in Dallas history, the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. When he previously worked in Fort Worth in 1950-51, we lived in an apartment building whose landlady was… Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother, Marguerite. Just weeks before the assassination, my grandfather bought a mail-order Italian rifle similar to the one Oswald used. In the chaos of the days after the assassination, my father saw Jack Ruby in the City Hall press room talking with police officers and other reporters. My dad called aside the ranking police officer and objected – Ruby had no business being there. Nothing was done. The next day, in the basement of that same building, Ruby shot Oswald. Later my dad testified about some of this at Ruby’s trial.

I can vouch these are facts, as my dad related them. The coincidences are more suspicious and strange than any I’ve seen in a dozen conspiracy theories. And yet – there is no conspiracy lurking behind them.

Strange coincidences could just mean that life… is strange.

Untangling the End Times

Christians believe the biggest conspiracy of all is spiritual and being played out on a galactic scale. It’s not secret since it’s described in the Bible. But it’s the minutiae and fine print that can derail one’s reason.

Milton’s Paradise Lost portrays the rebellion of Satan and his fallen angels against God as a conspiracy, an image influenced by the Guy Fawkes Gunpowder Plot that unfolded in Milton’s youth. Like the later whispered words of the serpent to Eve, it forms the beginning of what most Christians believe to be a spiritual conspiracy of active evil against good. Though the outcome of this rebellion is revealed by God’s victory in the Book of Revelation, the everyday spiritual warfare is ongoing. But this general outline often provides the template for more mundane conspiracy theories about politics, science or historical events.

In the past, the target or villain of the story was usually the suspicious outsider, those on the fringes of society – Jews, Gypsies, old poor women (witches), ethnic minorities – who were accused and became the scapegoat (see the writings of Rene Girard). With QAnon, it is the equally distant but powerful insiders at the other end of the social scale who are suspect, fueled by popular resentment and envy.

The mother to conspiracy theories, I think, has been the attempt over centuries to tease out and interpret the intricacies of prophetic fulfillment from biblical texts.

My eyes were opened to my own tendencies toward this kind of “selective perception” after I had been obsessed for years with biblical prophecy and its fulfillment in current events. Was Henry Kissinger the Antichrist? Was the 1967 Arab-Israeli War a sign of the end times? Was Soviet Russia the Magog of Ezekiel’s prophecies? Was the European Common Market the 10-headed Beast of Revelation? It provided fuel for endless hours of speculation.

After 50 years, though, these players have all been replaced several times over. So, is Bill Gates the Antichrist now? What about 9/11? Putin? The EU now has 28 members, not 10. And what about Brexit? Hal Lindsey, author of The Late, Great Planet Earth, is still publishing books about all this, even as all his original puzzle pieces and geopolitical arrangements have changed over the decades. It never ends, and it’s always in flux.

One day I came across an old theology book missing its cover, published in the 1800s that pinpointed the Ottoman Empire as the Beast of the Book of Revelation through a carefully reasoned interpretation of the scriptures. I’m sure it seemed logical at the time.

(Of course, the conspiracy mindset never rests. Recent pining for Ottoman glory by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has revived this very theory among some flexible biblical eschatologists).

I finally gave up on finding prophetic fulfillments in current events, and left it to God to sort out.

Truth and Light

One of my dad’s first jobs was as a reporter for The Fort Worth Press. As a Scripps-Howard paper, it carried that chain’s lighthouse logo and the slogan, “Give light and the people will find their own way,”

When I was studying journalism, I once brought up that slogan. My dad laughed. He reminded me that Jesus was the Light of the world, not Scripps-Howard. And even so, it didn’t seem to him that many people were choosing to “find their own way,” even with the natural light that they were already given.

But as I reflect on it now, there actually is a connection between the two. You’ve got to have a concept of truth, both to understand the gospel as well as to get to the bottom of what’s taking place in our world. Without a concept of truth, we’re all just standing on air.

What is Truth?

When the founders published the Declaration of Independence they expected its readers would rely on commonly accepted standards of truth to judge the rightness of their cause – a worldview shaped by Judeo-Christian values, Natural Law, and Enlightenment ideas of reason.

George Washington, in many of his private letters, invoked Micah 4:4 in his vision of each American “sitting under his own vine and fig tree.” It was meant to be a picture of individual freedom and security.

But today we seem to be each sitting under our own subjective version of the truth, sheltered by our own individual self-justifications, isolated from others and cut off from accountability, and accusing our neighbor who disagrees with us, even throwing stones at him over there where he sits under HIS vine and fig tree. That’s nonsense and delusion, and a prescription for social chaos.

The first Christians, while asserting they looked to the scriptures alone for truth about salvation, were remarkably broadminded in their sources of truth for other purposes. Early church leaders like Ambrose approved of “robbing” the classical authors and philosophers of earthly truth and wisdom, just as Israel had “robbed Egypt” in the Exodus.

St. Augustine, in his On Christian Doctrine, for example, wrote, “Nay, but let every good and true Christian understand that wherever truth may be found, it belongs to his Master…” In other words, all truth is God’s truth.

During the Reformation, John Calvin approved this position: “If we reflect that the Spirit of God is the only fountain of truth, we will be careful, as we would avoid offering insult to him, not to reject or condemn truth wherever it appears” (Institutes, II.2.15).

Many of my Christian brethren say they want to debate or disagree about issues reasonably and with civility. But by refusing to acknowledge scientific facts, denying “expertise” or any common standards by which to evaluate information, or refusing to listen to a source just because it is from an opposing political camp, they are on a precipice. While believing they are clinging to the truth, they are – without realizing it – falling into a position akin to a postmodern relativism, where critical thinking is futile and anything goes, nothing is real, and nothing can be proven.

(And we should find that much scarier than “socialism”).

In Hannah Arendt’s 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, she asserts,“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction . . . and the distinction between true and false . . . no longer exist.”

The bottom line for any Christian believer should be truth with a capital “T.” The New Testament explains that Jesus is Truth, while Satan is the “father of lies.”

Of course, we’re also sent out “as sheep in the midst of wolves” to be “wise as serpents and harmless as doves” (Matthew 10:16).

But Christians who slander people (even politicians) and spread rumors without evidence are not only failing to be wise, they are causing harm.

Don’t Be Careless With The Truth

In summary – there is increasing dispute in politics, science, philosophy and the news media, not just over different opinions or policies or theories, but over what constitutes actual facts.

We’re finding ourselves with no solid, agreed-upon basis for determining what is true and what is false. And we don’t seem to care.

When Christians are careless with the truth just because a Facebook meme supports our preconceived opinions, in a way we’re betraying Christ as surely as Judas did. Truth matters, across the board.

As Jesus stood before Pontius Pilate, they had a discussion about truth. Pilate asks Jesus if he considers himself to be a king. Jesus replies that He came into the world to “bear witness to the truth. Every one that is of the truth hears my voice.”

Pilate, the veteran of years of Roman political intrigue and infighting, ponders Jesus’ answer: “What is truth?” he asks, to no one in particular. Then he “washes his hands” of the whole question.

“Quid est veritas?” The question still hangs in the air 2,000 years later.

And we each will have to answer that question for ourselves.

See all the old archived, classic Rick Perry Devotionals here!

See all the old archived, classic Rick Perry Devotionals here!