- “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald

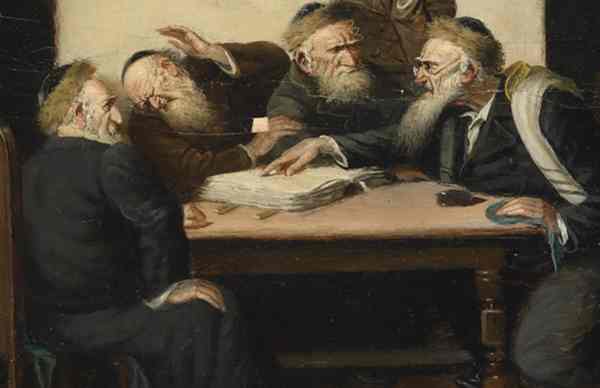

Now there’s a meme you will rarely see on Facebook. But it’s a truth the rabbis understood and took to heart.

The Talmudic rabbis challenged us to “Make your heart into many chambers” so we can hold opposing views and see things from another person’s perspective.

But too often in social media posts the author’s heart is stuffed with only one possible position – his own.

From the Pirkey Avot in the Mishnah: “Any argument that is for the sake of Heaven, in the end it will succeed; any argument not for the sake of Heaven will in the end not succeed.”

That Hebrew term “succeed” or l’hitkayem doesn’t necessarily mean “to win.” It carries the sense of “existing,” as in “the argument will continue to exist.”

An argument taken up “for the sake of Heaven” – i.e. for ultimate Truth and Goodness – will in fact never end. It will never cease to exist. As long as both parties push each other toward a truth that is greater and more profound than any small-minded agenda either party could bring to the table, then the argument itself – the mahloket – will keep producing holy meaning, holy energy.

Truth is Revealed in the Journey

The Hebrew word for truth – emeth – begins with the first letter of the alphabet, ends with the last letter, and they are joined by the middle letter of the alphabet. The rabbis understood this to mean that truth is not just where everything begins, not just where everything leads to, but also truth is in the journey to get there. In fact, the Bible is filled with argument – between God and Abraham, between Moses and Aaron, between God and Job, etc.

The 1st century B.C. rabbinical schools of Hillel and Shammai often disagreed. This passage is from the Tosefta, an early version of the Mishnah:

“One may say to oneself, ‘since the House of Shammai says “impure” and the House of Hillel says “pure” – one prohibits and one permits – why should I continue to learn Torah?’ Therefore the Torah says, d’varim, had’varim, eleh had’varim – ‘words, the words, these are the words’ (Deuteronomy 1:1). All the words were given by a single Shepherd (Ecclesiastes 12:11), one God created them, one Provider gave them, the Blessed Ruler of all creation spoke them. [Babylonian Talmud, Hagigah 3a] Therefore, make your heart into a many-chambered room, lev hadrey hadarim, and bring into it both the words of the House of Shammai and the words of the House of Hillel, both the words of those who forbid and the words of those who permit.” [Tosefta Sotah 7:12]

Rabbinical argument was all about finding truth in the scriptural text – different from the Greek rhetoric of the Sophists, who would use verbal tricks and flowery oratory to sway a political rally or convince a courtroom.

Rabbinical dialogue consisted of a series of arguments, a “shakla v’tarya.” A give and take. Parry and thrust. The thrust was your argument. The parry was your response to the other party’s argument. To “parry” effectively, you had to actually listen.

Arguing with Humility

The kinder, gentler tone of Hillel won out eventually. The reason? Humility:

In a Talmudic passage [Eruvin 13b] we read, “Why was the law set according to the House of Hillel? Because they were gentle and humble (nohin v’aluvin hayu) and they taught both their own words and the words of the House of Shammai. And not only this, but they taught the words of the house of Shammai before their own.”

The continuation of the argument meant it was held together by love. It meant remembering that your opponent possesses the tzelem elohim, that “divine image” each human reflects. “Heresy” would be to leave the conversation because you were done listening, or if you had demonized the other as an enemy, or left off dialogue to personally vilify the other party.

An example of this happened in Ephesus with the Apostle Paul, who was trained as a Pharisee in rabbinical argument:

- Acts 19:8-9 – “And he went into the synagogue, and spake boldly for the space of three months, disputing and persuading the things concerning the kingdom of God. But when divers were hardened, and believed not, but spake evil of that way before the multitude, he departed from them, and separated the disciples, disputing daily in the school of one Tyrannus.”

Paul was “disputing,” = dialegomai (reasoning) and “persuading” = peithō (to convince by argument). But eventually some of his opponents were “hardened” = sklērynō (from a root that means hard, or rough, and can imply violence), and they began to try to stir up the crowds against him. So he took the discussion to a more neutral location to continue the dialogue.

The love of truth was replaced by a demonizing of the other. For Paul’s opponents, the dialogue was over.

Social media is not the best forum for closely reasoned argument. But nevertheless, we can approach opposing opinions with “a heart of many chambers” in order to absorb a multiplicity of ideas and opinions – and in order to remain open to correcting our own position before it ossifies in place.

Preaching to myself here, but when we label someone as stupid, an idiot or a fool – even mentally – we’ve already left the path of understanding and truth.

There’s also a warning: We don’t stop contributing to the dialogue, the mahloket, just because we find it too frustrating or hopeless. Or because the discussion seems to be steering us to take a stand where we’ve been able to avoid taking a stand before.

Speaking truly and honestly, as well as listening deeply and patiently, supersedes mere civility or politeness. It’s the outworking of the command to “love your neighbor as yourself” taught by both the Torah (Leviticus 19:18) and by Jesus (Mark 12:31).

– I drew from and adapted many of the ideas for his essay from “A Heart Of Many Chambers” by Rabbi Lester Bronstein, The Orchard, Fall 2014, which can be found here

See all the old archived, classic Rick Perry Devotionals here!

See all the old archived, classic Rick Perry Devotionals here!